Some readers might recall that Dr. Ken Long and I developed a Systems Thinking Workshop last summer. The initial reason for that course was that Ken Long has a master’s degree in systems thinking and a doctoral degree in decision making under uncertainty. We realized that a good understanding of systems thinking really helped people understand Ken’s systems better. I delivered the second version of the systems thinking course at the annual Super Trader Summit last year and that experience really helped me understand it and even evolve it more. Little did I know, until I’d taught the course, how much systems thinking is a part of the way I already perceive the world. In fact, my approach might be a slight evolution beyond common ideas now adopted by systems thinking and I’ll try to explain that in this article.

So first let’s talk about paradigms or world views. There have been three major paradigms in operation since the time of Aristotle, around 300 BC. These include: the Traditional View of Knowledge, the Scientific Approach, and the Systems Approach. In addition, I’ve been advocating a move beyond systems theory to what I will call for simplicity, the Matrix Approach.

Paradigm One: Aristotle and the Bible — The Traditional View of Knowledge

These include a hierarchical ontology where original Greek philosophy and the Bible were the ultimate authority. What was known must be endorsed by tradition. And for this very reason, this paradigm lasted for almost 2000 years. The authority for almost anything was the accepted science before the church (and was basically what Aristotle believed), what the Bible basically said (plus the Pope, various saints, and authorities in Catholic Church would agree to), and finally what the King of any nation said was true. If you questioned such knowledge or the authority upon which it was based, you risked being called a heretic at best and being tortured and burned at the stake, condemned to eternal hell, at the worst. And being condemned to hell was sort of assumed to be your fate once you were labeled a heretic. Thus, you might have disagreed with this world view, but you were not likely to do so publicly. And if even if you did that, you were not likely to publish and disseminate your beliefs and observations.

Let’s look at what Aristotle thought about the Universe to illustrate this approach. The earth was the center of the universe. Gravity could be explained because things fell to the center of the universe. And the orbits of the known planets could be explained by assuming that there were approximately 80 crystalline spheres to explain the various orbits of planets. The outermost sphere contained all the stars not known to be planets. And because of the way it was set up, you could not question authority, the theory lasted for about 2000 years.

Economic advancement was difficult under this model because, for one thing, the scriptures said that borrowing and lending was a sin. And if you did lend, you certainly couldn’t collect interest on your money, so who would want to lend. The king, as an authority, could basically take whatever he wanted. The church was exempt from this and it could also take what it needed in terms of tithing.

Paradigm Two: The Scientific Method and Its Emphasis on the Objective

I was indoctrinated in this paradigm as a student of psychology between 1965 and 1975, even though the new systems paradigm had already taken over — at least in physics.

First, it assumes that the world is physical and that knowledge comes from empirical observation.

Second, it assumes that laws are written in mathematical language and that the primary characters of science are geometric forms.

Third, it was firmly assumed that the objective (that which could be observed and measured) ruled over the subjective domains.

Fourth, the world (or whatever was being studied) was broken down into various parts and each part was studied by itself.

It was thus assumed that the whole was equal to the sum of its parts.

Causation was linear and occurred in a specific time sequence. In other words, X happens at one point in time and it causes X at some later point in time.

Sir Isaac Newton basically developed a complete scientific and mathematical framework for physical systems. He believed that time and space were fixed coordinates. That the world was governed by discrete components of matter interacting in a cause and effect manner. And the net results were the assumption of a completely predictable and deterministic world if you just had enough information to know how everything impacts everything else in a linear fashion.

The study of science, according to this paradigm, might be called reductionism. You could understand everything by just breaking it all down into component parts and understanding how those parts worked. You just needed to control all the variables (keep them constant) except for the few that you considered important. And if you manipulated certain variables, then you could predict certain things would happen. You always had to exclude changing environments so that experiments could be replicated.

Science progressed because now it was understood (and accepted) that the earth revolved around the sun. That gravity was based upon the mass of a particular object. That force was equal to mass times acceleration. And with these and a number of other observations, one could begin to predict both the terrestrial and the celestial worlds.

When I went into psychology, I wanted to understand how human beings think. I wanted to know how to model things. But the outstanding paradigm of the day, while I was in school, was behaviorism. You controlled such things as the input (stimulation and reinforcement) and then you observed the response you got. And you didn’t care what went on inside the black box (i.e., the brain) because that would be getting into the subjective.

Well, I did care about what went on in the black box. I wanted to know how we thought. I wanted to know how to model certain skills. And since psychology was treating the human being as a black box, I went into biological psychology so I could study the brain. Unfortunately, the same paradigm was being used. If you stimulated this part of the brain, what happened? If you cut that part of the brain, what happened or what was missing. But it was the same model and I was not happy with it at all.

In terms of trading, however, you can get a little more specific with this paradigm. You can break down a trading system into its parts. You can look at set-ups, entry, initial risk, exits, and position sizing. And when you understand each component, well perhaps you can begin to make money.

Paradigm Three: Systems Theory and the Holistic Approach

The third paradigm shift began early in the 20th century with Einstein and relativity and the almost simultaneous development of quantum physics. A number of critical things began to change with these paradigm shifts including:

The subjective suddenly became at least as important as the objective because knowledge was suddenly assumed to be an interaction of the subjective and the objective. You had to understand the role and the impact of the observer.

Second, it was assumed that you must know the assumptions of the paradigm you were using because the paradigm itself could distort the process. This meant asking 1) how do I see the world; 2) how do others see the world; and most importantly, 3) how do those models shape and create the world we see?

Suddenly, scientists could understand the world as a feedback loop. We have met the enemy and he is us.

With this new paradigm shift, suddenly the whole was the most important. What is the impact of the environment — the context. What are the interactions with other systems that might be involved? And all of this opened up the possibility of non-linear causation or multiple causation where the time element wasn’t important because feedback loops in the future could influence the outcome.

Within systems theory the idea of emergence becomes paramount. You cannot understand the whole as a sum of its parts because quite often the whole is much more than the sum of its parts. For example, if you combine hydrogen and oxygen, you get water. But the liquid properties of water (at least under a certain range of temperatures) is not something you could predict from either hydrogen or oxygen alone.

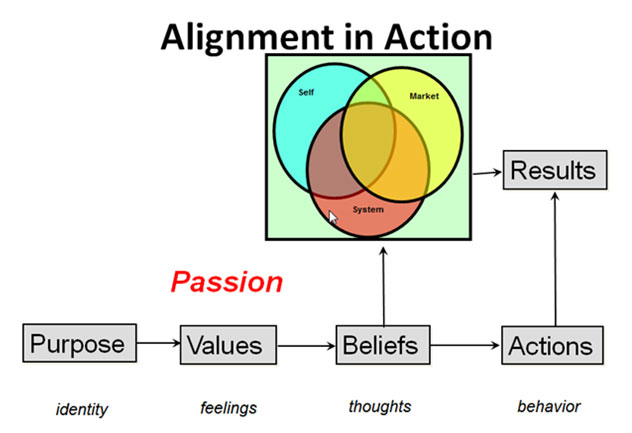

With this kind of approach, we can suddenly begin to understand that trading involves the interaction of the self, the market, and one’s trading system. And it’s the intersection of those parts that leads to success or failure in making profits in the markets. This is shown in the following diagram which you have likely seen many times at the Van Tharp Institute.

Now suddenly with a systems approach, context becomes very important. We must look at the context for each system. What is the market type? What is the system type? And what is the state out of which the trader is operating? These all become important to trading results. And, as a result, we begin to understand such Tharp Think rules as 1) it possible to design a holy grail trading system for any one market type; but 2) it is insane to expect that trading system to work well in all market types.

Paradigm Four: The Matrix Approach

At present, I think there is a fourth paradigm emerging. It’s probably the most useful paradigm of all, but it is not widely accepted. And it differs from the systems approach in that it stresses the subjective as being much more important than the objective. Its fundamental assumption is that the map is not the territory. And that means that all we ever know is the subjective because the real world — if it even exists — can only be known through sensory systems that filter real world information and language that wires our brains to assume that the world is made up of subject, object and verbs. It also tends to turn processes or verbs into nouns. So reality (which is only a process of trying to decide what is real at any given instant) becomes a noun reality and that is assumed to also be real.

Within this framework, which I call the Matrix Model, all we can know is our models of the world. But we can determine through these models how others behave and develop models whereby we can be more successful. However, we must always understand that those models are not real, just useful. And that means that there can always be something more useful than what we have right now.

With respect to trading, suddenly we get the notion that the market itself isn’t real — because it is a nominalization. Everything we use to represent the market — charts, moving averages, and various indicators are all made up. And therefore, we can only trade our beliefs about the market. We know that our beliefs are useful because useful beliefs tend to make money.

My understanding is that only about 20% of the population is able to understand systems thinking. So if you start to think to yourself; “Everything Van says is ridiculous. I’m an engineer. I can observe the market and program trading systems and make money.” My response is, yes, that’s quite possible. But if you think that way, chances are you don’t understand systems thinking yet and are still stuck in the second paradigm — the old science paradigm that was gradually replaced nearly 100 years ago, but still tends to be taught because it’s just easier to think that way. Just be careful and do so at your own peril.