Last week was rough for investors, to say the least:

Last week was rough for investors, to say the least:

- Yield-curve inversion

- 800-point drop in the Dow

- Trade war uncertainty

- Unrest in Hong Kong bringing down Asian markets

- Argentina’s stock market dropping 48% in a single day on fears of another debt default

That’s enough to make anyone want to take a break. But the market doesn’t wait for anyone, and this week promises to be no less eventful, with tweets already flying from the White House and Fed Chair Jerome Powell speaking at the Fed’s own Jackson Hole Symposium on Friday.

Investors will be hanging on his every word to determine what the Fed will do next.

But first, let’s talk about the big market news from last week, Wednesday’s so-called “yield-curve inversion.” Despite the market’s one-day panic last Wednesday, there are several things to consider:

- Is the inversion even real?

- Do current central bank activities in Europe and Asia make this recession indictor less reliable or not important at all?

- Should this impact our trading or portfolio management at all right now?

There are Months of Profit Ahead

“Yield-curve inversion” has been all the buzz lately. The 2-year Treasury note’s yield exceeded the 10-year Treasury note’s yield for a short time last Wednesday.

In other words, investors wanted more money in return for holding a 2-year U.S. government bond than a 10-year one.

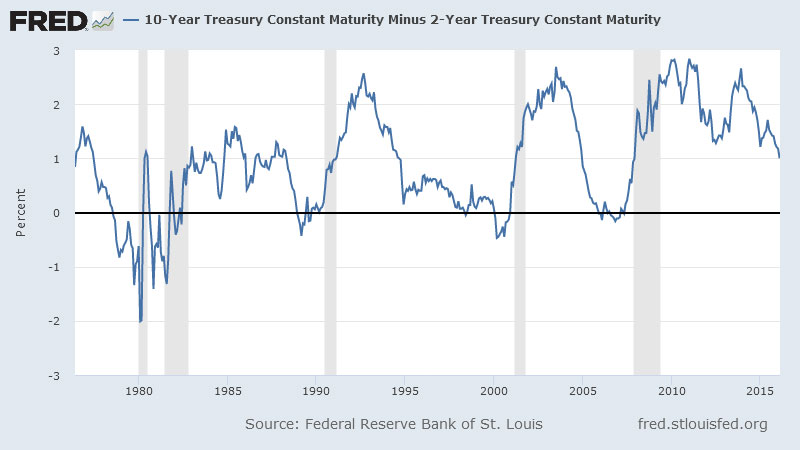

The markets did a one-day freak and here’s why. As you can see in the chart, every time the yield-curve has inverted (i.e. when the blue line dropped below the thick black line), a recession (the shaded columns) soon followed:

This relationship makes sense. You’d expect investors to demand a higher yield in return for lending their money to someone for a longer period of time. The longer someone has to pay you back, after all, the more unexpected things can happen (e.g., inflation could unexpectedly rise), and the less sure you can be that you’ll get your money back. So investors ask for more yield on longer bonds to make up for that risk.

When the relation flips upside-down, it means investors think future yields will go down enough to make up for this risk premium – usually because the Fed will push interest rates down. That, of course, happens when there’s a recession.

Was Wednesday’s Scare Even Real?

Wednesday’s yield-curve inversion only happened intra-day. In the morning, the 10-year note’s yield dropped below the 2-year notes, the markets reacted. But then the yield-curve flipped back to normal before market’s closed.

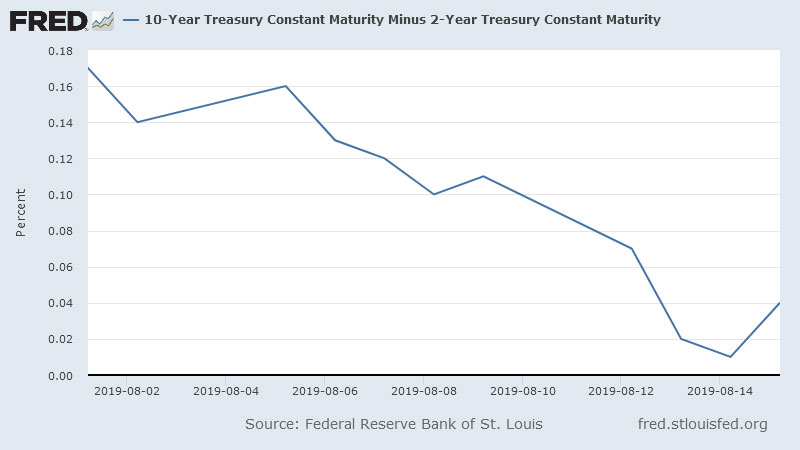

Here’s the St. Louis Fed’s chart again, zoomed in to this month:

As you can see, the blue line never went down below zero. Wednesday’s “yield-curve inversion” when we look back at end of day data, will look like it never happened.

So the original panic was real, but most analysts aren’t seeing the possibility of a U.S. recession for quite a while. With strong consumer confidence and retail spending contributing to a GDP that is running +2.0% currently, having a two straight quarters of negative GDP growth will take a while, with or without an inversion.

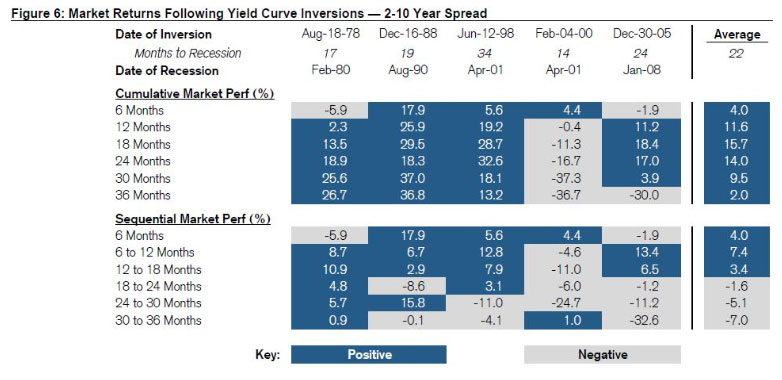

And even if the inversion does presage a recession, when the 2 and 10 year curves crossed in the past, stock prices have traditionally gone up for an average of 18 additional months. Here’s a table created by Credit Suisse looking at the five inversions since 1980:

And in my view, the inversion in February of 2000 has really just a follow-on of the inversion 19 months earlier; eliminating that inversion would make the data even more optimistic.

And Jonathan Golub from Credit Suisse cautions that other instances of yield curve inversion have other confounding factors. He writes,

“Historically, an inverted yield curve has been accompanied by a variety of other ominous economic signals including layoffs and credit deterioration.”

There’s another reason that casts some doubt on whether the 2/10 yield curve inversion is predicting a coming recession. This one was discussed by Mohamed El-Erian, the well-known economist for Allianz who used to run investment giant Pimco.

Because of the negative interest rates in Europe and Asia, El-Erian argues that the U.S. bond market is not like previous inversion cases. He told CNBC:

“So all that (negative yields in other countries) is going to distort our yield curve. And it’s going to weaken the traditional signaling mechanism” for a U.S. recession, El-Erian said.

So as the market braces for the comments coming from Fed Chair Powell on Friday from Jackson Hole, one thing you don’t need to worry about in the short- to intermediate-term is a recession just popping up. Check back in 12 months from now to see if 2/10-year interest rate have remained inverted. If so, then you can start winnowing your portfolio…

Great Trading and God bless you,

D. R.